Someone on the Facebook page of hegelcourses.wordpress.com stated an opinion: “I do not think there is any connection between property and freedom”. Hegel is then also wrong in making property the first category of Abstract Right. Now Hegel is of course discussing the foundations of modern society that is ultimately concerned with the free individual. The first appearance of freedom as an explicit concept, in the history of Western societies, is the Roman concept of the individual as an owner, who is distinguished from objects and therefore cannot be a property himself. That Roman legal distinction between free people – owners – and people that can be property – slaves – developed into the more modern concept of the (universal) free individual in the form of a Natural Law thesis. Roman Law is still the foundation for many law codes that developed since then, e.g. the Code Civil in France and later also the Civil Law of the Netherlands.

To use property as the most immediate concept of personhood is therefore legitimate because it is surely the case that Hegel was describing one of he main foundations of the modern state by using that category. That doesn’t mean however that he agreed with the notion that in modern societies this category is the only and universal principle, or similarly, that he agreed with the naturalist view by Hobbes and Rousseau that somehow the whole of society can be explained with the concept of “contract”.

There are contemporary philosophers that would disagree with the importance of this concept in a Philosophy of Law that do not want to merely explain the immanent rationality of modern society but want to express the moral foundations of sociality more forcefully and more directly. They want to talk about what should be, more than about what actually is. Such a philosopher might be someone like Emmanuel Levinas. What can we glean from him?

Emmanuel Levinas, a French philosopher known for his work on ethics and responsibility, does not address the concept of property directly in the same way that economic or legal theorists might. However, his philosophy has implications for understanding property in the context of ethics and human relations.

Levinas’s philosophy is centered on the ethical relationship between the self and the Other, where the face-to-face encounter with another person is the foundational experience of ethical responsibility. This encounter with the Other demands a response from the self, which Levinas sees as the essence of ethical behavior.

In terms of property, one could infer from Levinas’s work that the ownership of property would be secondary to the ethical obligations we have towards others. Property, like any material possession, could be seen as an extension of the self that enters into the ethical sphere once it affects the relationship with the Other. The ethical question would not be about the right to own property, but about how the ownership and use of property impact the well-being and dignity of others.

Levinas’s critique of identity and his emphasis on the primacy of ethics over law suggest that legal definitions of property and ownership might be challenged by ethical considerations. He signals an essential contradiction between the primordial ethical orientation and the legal order, indicating that justice, which includes the legal frameworks governing property, places limitations on responsibility, which at the same time it presupposes as its very condition of possibility.

For Hegel, a social philosophy that would start with this personal responsibility as the foundational category would no longer “stick to the facts.” It would have a utopian quality that belongs to the realm of ethical discourse about what should be. It would not be an analysis of what really is.

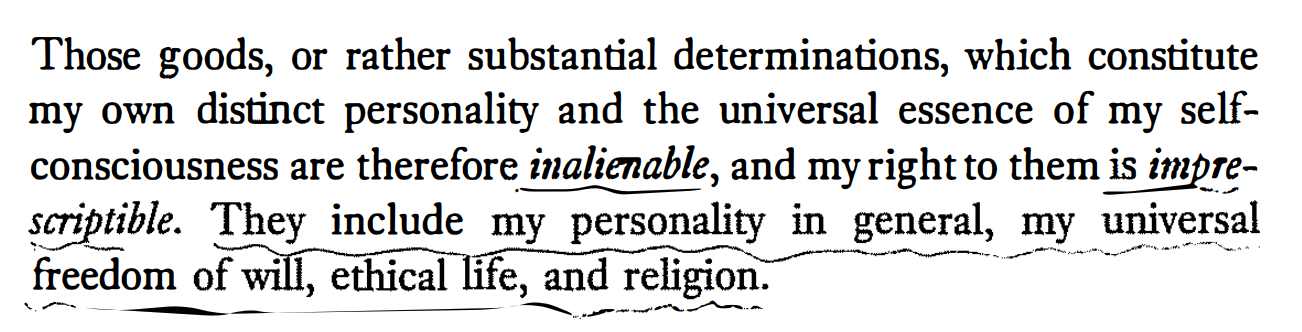

That does not mean that there is not some ground to argue that Hegel did not take into full account how the principles of property and contract might lead to injustice precisely by observing and guarding them in modern law. Property can be “theft”, a contract can be a deprivation of rights when people are in a position that does not really allow them to act freely. The implications of the needs of human beings might outweigh the rational institutions and practices of society. The Jewish approach to property, exemplified in the Talmoed tractates of the First, Middle, and Final “Gate”, is first and foremost concerned with “torts”, that is abuse of property, damages, and the area of deception in everyday commerce. In principle, all of these are also dealt with in Hegel’s chapter on injustice, which closes the first section of Abstract Right – Property, Contract, and Injustice. But one might consider this too late and too little in the face of the historical experiences of the impoverished masses of factory workers in the 19th century.

NOTE – Hegel does apply moral principles in his treatment of property. An example is his critique of Gustav Hugo who defended the immoral property laws of the Romans on historical grounds. Here is a summary:

Hegel critiques Gustav Hugo’s approach to the history of Roman law for its attempt to rationalize laws and regulations that are fundamentally unjust and inhumane, such as the right to execute creditors, slavery, and the treatment of women and children as property. Hugo justifies these on historical grounds, seeking explanations in the context of the times rather than assessing them against the standards of reason. In stark contrast, Hegel seeks to engage with Roman civil law in a way that acknowledges its influence on contemporary legal systems and addresses the foundations of legal rights in a society undergoing political and social transformation. He argues that the upheaval of historical events has infused Roman legal concepts with new intellectual substance, relevant to the modern world. This reformation has redefined the concept of a “person” in law, expanding the rights and freedoms to all human beings, making freedom a core principle of legal rights. Thus, Hegel’s perspective moves beyond historical justification to a critical engagement with law in the context of human rights and societal progress.